Nicaragua history is a complex tapestry woven from the threads of indigenous cultures, colonial conquests, struggles for independence, political upheavals, and social revolutions. From ancient civilizations to modern nation-building efforts, Nicaragua’s story is one of resilience, diversity, and struggle. In this detailed exploration of Nicaraguan history, we will journey through the key events, figures, and turning points that have shaped the nation’s past and continue to influence its present.

Pre-Columbian Era

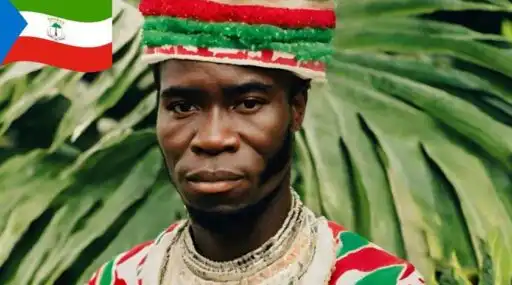

The history of Nicaragua begins long before the arrival of European explorers. The region was inhabited by various indigenous peoples, including the Chorotega, Chontal, and Nicaraos. These societies developed sophisticated agricultural techniques, built impressive cities, and engaged in complex trade networks. Notably, the Nicarao people gave their name to the country, with “Nicaragua” meaning “land of the Nicarao” in the Nahuatl language.

One of the most significant pre-Columbian civilizations in Nicaragua was the Chibchan-speaking people known as the Chorotega. They inhabited the Pacific coast and were renowned for their pottery, agriculture, and social organization. The Chontal people, who lived along the Caribbean coast, also left their mark on Nicaraguan history with their distinct cultural practices and maritime traditions.

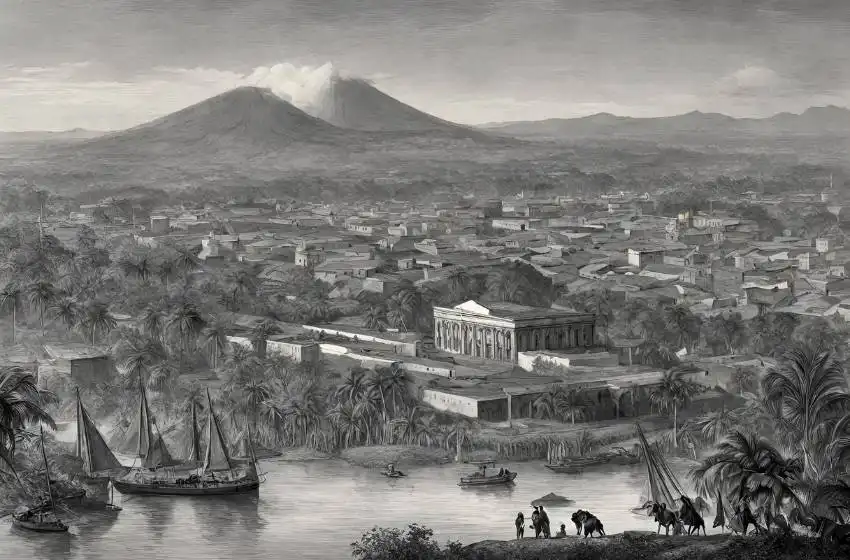

Colonial Period

The arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the early 16th century marked a profound turning point in Nicaraguan history. In 1524, the Spanish explorer Francisco Hernández de Córdoba led an expedition that resulted in the conquest of the region. The city of Granada was founded in 1524, followed by León in 1529, establishing Spanish colonial rule in Nicaragua.

Under Spanish domination, the indigenous populations were subjected to forced labor, exploitation, and diseases brought by the Europeans, leading to a drastic decline in their numbers. The Spanish also established large haciendas (plantations) for the cultivation of crops such as sugar, tobacco, and cacao, using enslaved indigenous and African labor.

Nicaragua was part of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, a Spanish administrative division encompassing much of Central America. However, the region experienced relative isolation due to its rugged terrain and lack of significant mineral wealth compared to other Spanish colonies.

Independence and Early Republic

Nicaragua’s path to independence was tumultuous and marked by internal conflicts and external interventions. In 1821, Nicaragua, along with other Central American territories, declared independence from Spain as part of the Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide. However, this union was short-lived, and in 1823, Nicaragua joined the United Provinces of Central America, a federation composed of five Central American states.

The period following independence was characterized by political instability and power struggles between competing factions. The rivalry between the conservative elite based in Granada and the liberal forces centered in León became a defining feature of Nicaraguan politics.

In 1838, Nicaragua seceded from the United Provinces of Central America and became an independent republic. The country’s first constitution was adopted in 1838, establishing a federal system of government with a president as the head of state.

Throughout the 19th century, Nicaragua experienced frequent civil wars, coups, and foreign interventions. The country became a battleground for competing regional powers, including the United States and Great Britain, vying for economic and strategic interests in the region. The construction of the Panama Canal in the early 20th century further heightened Nicaragua’s geopolitical importance.

American Interventions

Nicaragua’s strategic location and abundant natural resources made it a target for American expansionism in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The United States sought to assert its dominance in the region through military interventions, economic concessions, and support for friendly regimes.

One of the most infamous episodes in Nicaraguan history was the construction of the Nicaragua Canal, an ambitious project championed by American entrepreneurs in the 19th century. Although the canal was never completed, its development efforts led to widespread land expropriations, forced labor, and environmental degradation.

In 1909, the United States intervened militarily in Nicaragua to support the conservative government of José Santos Zelaya. This intervention marked the beginning of a period of prolonged American involvement in Nicaraguan affairs, characterized by political interference, military occupations, and economic exploitation.

The most notorious American intervention in Nicaragua occurred during the early 20th century under the administration of President William Howard Taft. In 1912, the United States Marines landed in Nicaragua to suppress a rebellion against the government of Adolfo Díaz, beginning a decade-long occupation that lasted until 1933. The U.S. occupation sparked widespread opposition and resistance from Nicaraguan nationalists, who viewed it as a violation of their sovereignty and independence.

Somoza Dynasty and Dictatorship

The 20th century witnessed the rise of the Somoza family, whose rule would come to dominate Nicaraguan politics for much of the century. Anastasio Somoza García, a former officer in the National Guard, seized power in a coup in 1936 and established a dictatorship characterized by corruption, repression, and human rights abuses.

The Somoza regime maintained close ties with the United States, which provided political and military support in exchange for favorable economic concessions and regional stability. Under Somoza’s rule, Nicaragua became a virtual dictatorship, with the National Guard serving as the regime’s enforcers and suppressing any dissent or opposition.

Anastasio Somoza García was assassinated in 1956, but his dynasty continued with his two sons, Luis Somoza Debayle and Anastasio Somoza Debayle, who succeeded him as president. The Somoza family ruled Nicaragua with an iron fist, amassing vast wealth and power while exploiting the country’s resources and suppressing political dissent.

Sandinista Revolution

The Somoza dictatorship faced growing opposition from various sectors of Nicaraguan society, including students, workers, peasants, and intellectuals. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), a leftist guerrilla movement named after Augusto César Sandino, emerged as the leading force of opposition to the Somoza regime.

The Sandinistas launched a popular uprising in 1978, leading to a protracted civil war that culminated in the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship on July 19, 1979. The victory of the Sandinista revolutionaries heralded a new era of hope and optimism for Nicaragua, promising social justice, economic equality, and political freedom.

The Sandinista government embarked on ambitious social and economic reforms, including land redistribution, literacy campaigns, and healthcare initiatives, aimed at improving the lives of ordinary Nicaraguans. However, the revolutionary project soon encountered opposition from various quarters, including conservative elements, business interests, and the United States.

Contra War and Civil Conflict

The Sandinista government faced mounting pressure from counterrevolutionary forces known as the Contras, who were backed and financed by the United States. The Contra insurgency, which began in the early 1980s, plunged Nicaragua into a bloody civil war that lasted for nearly a decade.

The Contras carried out a campaign of sabotage, terrorism, and guerrilla warfare against the Sandinista government, targeting civilian infrastructure, government officials, and supporters of the revolution. The conflict resulted in widespread human rights abuses, displacement, and economic devastation, exacerbating Nicaragua’s already precarious socio-economic conditions.

The Contra war also had significant geopolitical implications, with Nicaragua becoming a battleground in the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Reagan administration portrayed the Sandinistas as Soviet proxies and provided extensive military and financial support to the Contras, further destabilizing the region.

Return to Democracy

The Contra war took a heavy toll on Nicaraguan society, contributing to widespread disillusionment and fatigue with the Sandinista government. In 1990, Nicaragua held free and fair elections, which resulted in the victory of Violeta Chamorro, the candidate of the National Opposition Union (UNO), a coalition of anti-Sandinista parties.

Chamorro’s election marked a peaceful transition of power and the beginning of a new chapter in Nicaraguan history. Her government pursued policies of reconciliation, national unity, and economic reconstruction, seeking to heal the wounds of the past and chart a path towards democracy and development.

Since the 1990s, Nicaragua has experienced periods of political stability and economic growth, interspersed with episodes of social unrest, electoral disputes, and authoritarian tendencies. The Sandinista party, under the leadership of Daniel Ortega, has returned to power, winning successive elections and consolidating its control over the country’s political institutions.

Current Challenges and Prospects

Today, Nicaragua faces a myriad of challenges, including poverty, inequality, corruption, environmental degradation, and political polarization. The government of Daniel Ortega has been criticized for its authoritarian tendencies, crackdowns on dissent, and human rights abuses, leading to international condemnation and sanctions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated Nicaragua’s socio-economic woes, straining its fragile healthcare system and exacerbating poverty and unemployment. The government’s response to the pandemic has been widely criticized for its lack of transparency, misinformation, and inadequate measures to contain the spread of the virus.

Despite these challenges, Nicaragua remains a resilient and vibrant nation, endowed with rich natural resources, cultural heritage, and human capital. The country’s young population, entrepreneurial spirit, and potential for innovation offer hope for a brighter future, provided that the government embraces democratic reforms, respect for human rights, and inclusive economic policies.

In conclusion, the history of Nicaragua is a testament to the resilience and perseverance of its people in the face of adversity. From the ancient civilizations of the pre-Columbian era to the struggles for independence, revolutions, and civil conflicts of modern times, Nicaragua’s story is one of triumphs and tragedies, dreams and disappointments. As Nicaragua continues to navigate the challenges of the 21st century, it is essential to remember the lessons of its past and work towards a future of peace, prosperity, and justice for all Nicaraguans.

Leave a Reply